Marie Feodorovna: A Life of Contrasts

The life of Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna (1847-1928), mother of the last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, and sister of Britain’s Queen Alexandra, begins as the story of a real-life Cinderella when an obscure Danish princess is catapulted into the extravagant world of Imperial Russia, which she effortlessly conquers.

Marie Feodorovna’s story ends in exile, as the last remaining symbol of the Russian monarchy, devastated by the Russian Revolution of 1917.

This post contains affiliate links, including links from the Amazon Associates programs. These links will direct you to products I recommend for further exploration and enjoyment of the topics I cover on my website and in my lectures. See more in the Privacy Policy below.

Marie Feodorovna’s Early Life

Princess Marie Sophia Fredericka Dagmar of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, known always as Princess Dagmar, was the daughter of Prince Christian of Denmark, who became King in 1863.

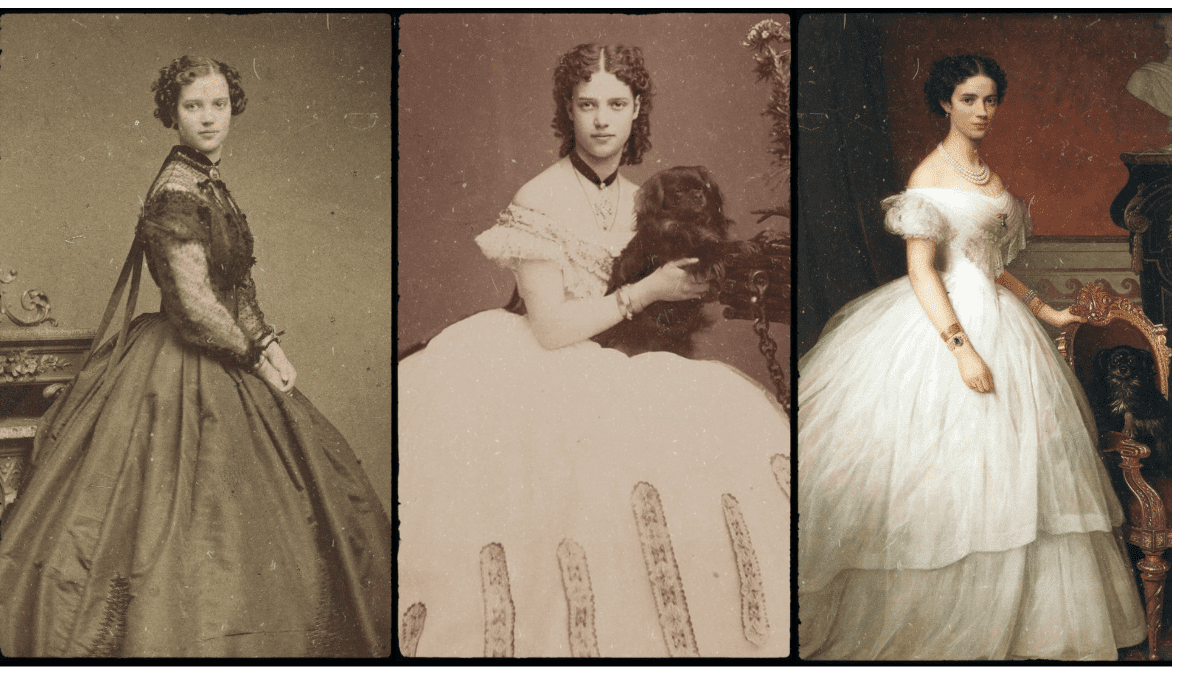

Marie Feodorovna as a young girl

Dagmar and her brothers and sisters grew up in happy if relatively modest circumstances for a royal family, and even after the accession of their father, the princesses did much of the housework themselves: skills they would not require in adulthood.

Europe’s Royal Politics

European politics in the Victorian and Edwardian eras focused on keeping fights from breaking out amongst a large, far-flung, and cantankerous family. The ultimate referee was “The Uncle of Europe,” Edward VII, who skillfully massaged the complex family ties forged by his parents, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, between their children and the scions of the reigning houses of Europe.

Listen to my interview with Corynne Hall, author of the definitive biography of Marie Feodorovna, Little Mother, about her latest book: Queen Victoria and the Romanovs.

These alliances had a decidedly Germanic bent: Edward’s older sister, Princess Vicky, mother of Kaiser Wilhelm II, married the heir to the Kingdom of Prussia; their younger sister Alice married the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt and produced Princess Alicky, who married Nicholas II of Russia.

For Edward, however, Victoria and Albert wisely made an aesthetic, rather than a political choice: Dagmar’s older sister Alexandra, the most beautiful princess in Europe, became Princess of Wales in 1863.

Maria Feodorovna: The Sea-King’s Daughter

Daughter of the King of Denmark, and sister of the Princess of Wales, Dagmar’s prospects as a potential royal bride increased. While not as classically beautiful as Alexandra, Dagmar was pretty and lively, and it was not long before royal suitors began to pay court, and none more ardently than Grand Duke Nicholas “Nixa,” the eldest son and heir of Tsar Alexander II of Russia.

Nixa embodied everything a 19th-century princess required of her Prince Charming: he was handsome, romantic, and heir to the vast, colorful, wealthy, and powerful Russian Empire. Dagmar accepted his proposal in 1864, and began at once to take instruction in the Russian Orthodox faith and Russia’s language and culture. She was generally agreed to be, as Queen Victoria articulated, “very fit for the position in Russia.”

Marie Feodorovna Turns Tragedy into Triumph

Events took a tragic turn. The following year, Nixa, whose health had always been delicate, collapsed in Nice. Dagmar raced to join the Imperial family at his deathbed, where, according to accounts, Nixa begged her to marry his younger brother Alexander, now the heir. Dagmar eventually agreed in 1866, transferring her affections from romantic and ethereal Nixa, to the more down-to-earth, robust, solid, and stubborn Alexander

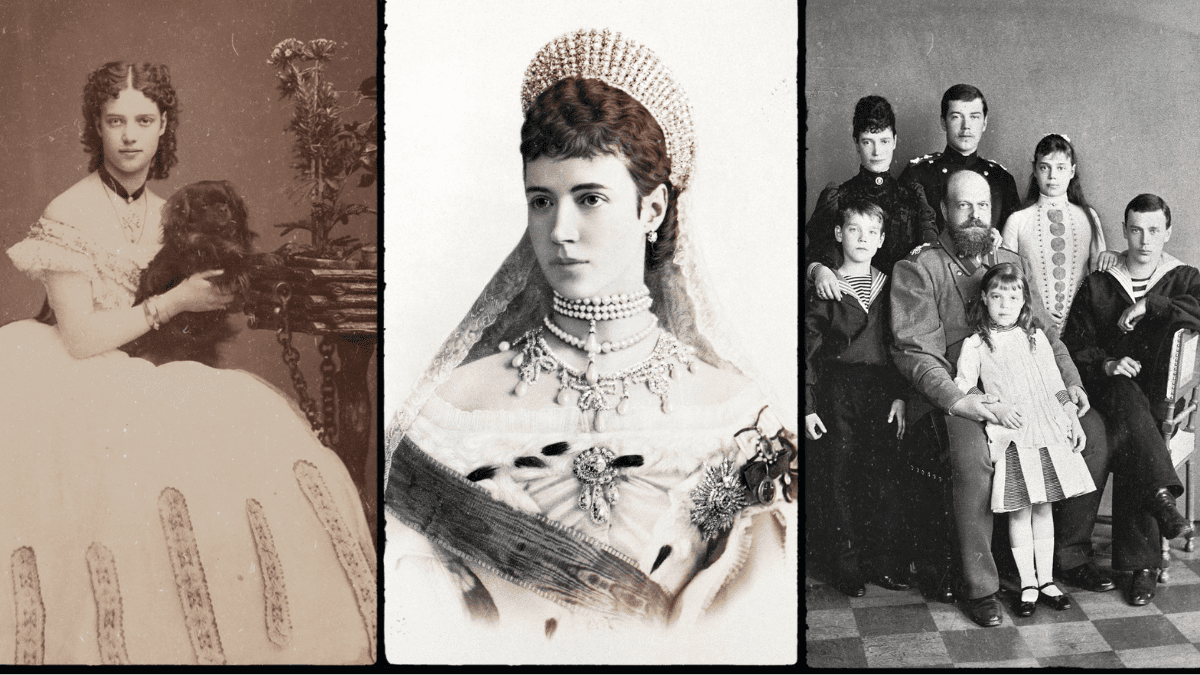

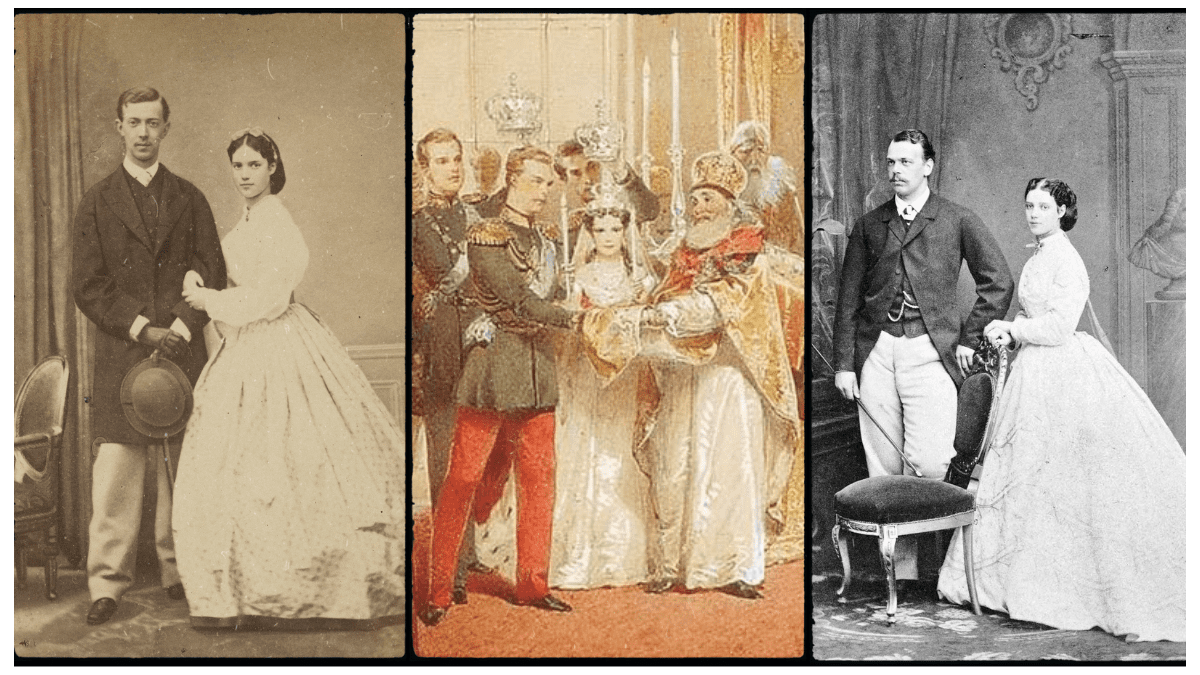

Two Engagements, and one wedding. Left: Princess Dagmar and her fiance, Tsarevich Nicolas; Center: Marriage to Grand Duke Alexander; Right: Engaged to Grand Duke Alexander

Dagmar’s story captivated all of Europe, and would later be the main precedent paving the way for the marriage of Edward and Alexandra’s son, George, Duke of York (later George V), to his deceased brother’s fiancée, Princess May of Teck (later Queen Mary) in 1893.

Grand Duchess Marie Feodorovna

Dagmar, now formally known as Grand Duchess Marie Feodorovna, but always called Minnie in the intimacy of the family, threw herself into Russian life with gusto. She lived in The Anichkov Palace on Saint Petersburg’s main thoroughfare, Nevsky Prospekt, and as Grand Duchess, she was at the center of Russia’s opulent social life, frequently called upon to deputize for her delicate and sickly mother-in-law, the Tsarina.

Marie Feodorovna, center, holds her son Nicholas. From left: Grand Dukes Paul and Sergei. Seated: Tsar Alexander II. Grand Duchess Maria, Grand Duke Alexis, Grand Duke Alexander, Grand Duke Vladimir.

Marie Feodorovna slipped into the Romanov family easily, befriending the Tsar and Empress’s only daughter, Maria, who would later marry one of Queen Victoria’s sons, and her four brothers-in-law: Vladimir, Alexis, Paul, and Sergei.

Childbearing, which seemed to exhaust the Princess of Wales, only increased the Grand Duchess’s robust good health. Nicholas was born in 1868, followed by Alexander in 1869, who died in 1870, George in 1871, Xenia in 1875, Mikhail in 1878, and finally Olga in 1882.

Marie Feodorovna: Empress of All the Russias

In 1881, Marie Feodorovna’s father-in-law, Tsar Alexander II, was assassinated, by members of the revolutionary group, “The People’s Will,” who threw a bomb into his open carriage. The Tsar’s legs were blown off and he bled to death that afternoon in the Winter Palace.

For the new Tsar and Empress, security became a primary concern, and they moved to the suburban estate at Gatchina, where entire regiments of soldiers and plain-clothed police officers surrounded them.

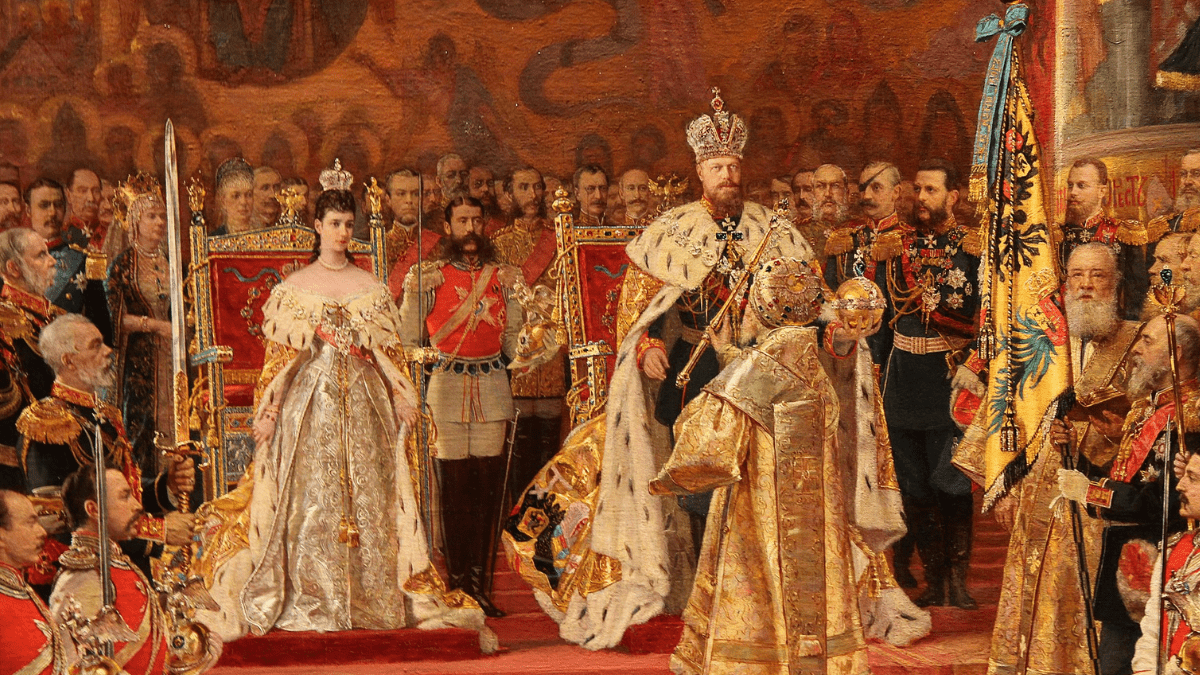

The coronation of Alexander III and Empress Marie Feodorovna

The Imperial Family found respite from these taxing security measures during relaxed autumnal visits to the Danish Royal Family at Fredensbourg. The informality of Fredensbourg enhanced the close ties of the Waleses and the Romanovs. Their children were good friends, and much was made of the astonishing resemblance of the future King George V and Nicholas II, who were often mistaken for one another.

Chancellor Otto Bismarck of Prussia regarded these apolitical gatherings with much suspicion, concerns he shared with his protégée Prince Wilhelm, the future Kaiser. The seeds of conflict were sown.

Join my Newsletter Community

Twice monthly, I’ll send you a digest of my latest articles and posts, travel and food news, and exclusive recommendations you won’t find anywhere else!

Marie Feodorovna: The Darling of Society

Elegant, intelligent, and consummately charming, Marie Feodorovna presided over the most glittering court in all of Europe, always impeccably dressed. She loved clothes and wore them so superbly that she was considered the best-dressed woman in Europe.

Julia Gelardi, in her excellent study of four Romanov women, From Splendor to Revolution: The Romanov Women 1847 – 1928, includes this anecdote about the relationship between Marie Feodorovna and Charles Frederick Worth, the renowned Parisian couturier:

“The famed Parisian couturier Charles Frederick Worth, from whom the empress often purchased her gowns, greatly admired Marie Feodorovna’s ability to carry off his creations. A high-ranking aristocratic lady once asked Monsieur Worth why he could not dress her in ‘the sublime triumphs that you make every week for the Empress of Russia?’ ‘Madame, it is impossible,’ answered Worth. ‘It is not enough that you pay me when your robe is accomplished… it is necessary first that you inspire me before your robe is begun here,’ tapping his brow and then his heart. ‘Her Majesty the Empress of the Russias, she gives me the inspiration sublime, divine, And when she carries my work she so improves it, I do with difficulty recognise it. Bring me any woman in Europe — queen. Artiste or bourgeois— who can inspire me, as does Madame, Her Majesty, and I will make her confections while I live and charge her nothing.’”

Marie Feodorovna’s love of fine things inspired her husband to commission Peter Carl Faberge to create the first of his incomparable Imperial Easter Eggs in 1885. The Hen Egg was the beginning of a tradition that Marie Feodorovna’s son, Nicholas II, would continue gifting eggs to his mother and wife until 1917.

Marie Feodorovna: Mother and Mother-in-Law

As Marie Feodorovna’s children passed from adolescence to young adulthood, her attention turned to finding them suitable partners. Unwilling to have her favorite daughter, Xenia leave Russia, Marie Feodorovna was relieved when Xenia’s choice fell on her second cousin, Alexander Mikhailovich, known to the family as Sandro.

From left: Marie Feodorovna with Alexander III and Grand Duke Michael; Center: Marie Feodorovna with her sons, Nicholas and George; right: Marie Feodorovna with Alexander III

Marie Feodorovna’s caused her more trouble; her second son, George, was diagnosed with tuberculosis as a teenager and sent to live in the Caucuses, where the mountain air was beneficial to his health.

Tsarevich Nicholas, the heir to the throne, usually biddable and pliant, proved unwavering in his determination to marry the shy, sullen Princess Alicky of Hesse-Darmstadt. Though neither Marie Feodorovna, nor Tsar Alexander III thought Alicky suited to the role of future Empress of Russia, they reluctantly gave their consent for Nicholas to propose to Alicky in 1894, at the wedding of Nicholas and Alicky’s mutual cousin, Princess Victoria Melita of Edinburgh to Alicky’s brother, Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse.

Egged on by another mutual cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Nicholas persuaded Alicky to overcome her concerns about converting to Russian Orthodoxy, and the couple announced their engagement to the entire assembled family, which included Alicky’s redoubtable grandmother, Queen Victoria.

Faberge was called in once again and earned his largest ever commission on the engagement present Alexander III and Maria Feodorovna gave Alicky: a sautoir (a long string necklace) of pearls that cost $2.9 million in today’s money. Even Queen Victoria was impressed, and reminded her granddaughter not to be “too proud.”

Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna

Marie Feodorovna spent much of the early 1890s fretting about her husband’s health. Alexander III was diagnosed with nephritis in 1894 and proved a difficult patient. In the autumn of 1894, doctors suggested a change of climate, and the Imperial Family headed to Crimea, hopeful that the milder Black Sea climate would do him good. But Alexander did not improve, and soon the Prince and Princess of Wales and Alicky were summoned to Livadia, along with other members of the family to support Marie Feodorovna as she presided over her husband’s last hours.

In the aftermath of Alexander III’s death, Alicky was accepted into the Russian Orthodox Church and became Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna.

Following the ordeal of a lengthy funerary procession from Crimea back to St. Petersburg, Marie Feodorovna oversaw the wedding of Nicholas and Alexandra in the Imperial Chapel of the Winter Palace.

Marie Feodorovna, now Dowager Empress, returned to her beloved Anichkov Palace with Nicholas and Alexandra, Xenia and Sandro, as well as her two youngest children, Michael and Olga. Relations with the new Empress were not easy: egged on by the Princess of Wales, Marie Feodorovna refused to hand over the crown jewels and insisted on retaining precedence over Nicholas’s wife on State occasions.

Marie Feodorovna: Grandmother

As the 1890s passed, Marie Feodorovna was active, both in St. Petersburg and around Europe. She joined the general national rejoicing in 1904 when Alexandra finally gave birth to a son and heir, Alexei, after producing four daughters in succession, none of whom could inherit their father’s crown. Marie Feodorovna relished her growing brood of grandchildren, particularly Xenia and Sandro’s seven children.

In his memoir Once A Grand Duke Sandro praised his mother-in-law’s zeal for amusements of all kinds.

“I don’t think even King Edward could have outdone my mother-in-law in willingness to participate in a bit of fun. Although I called her ‘mother’ and was well aware of her age, I considered her as my pal and associate when it came to going out to a party or to arranging a party.”

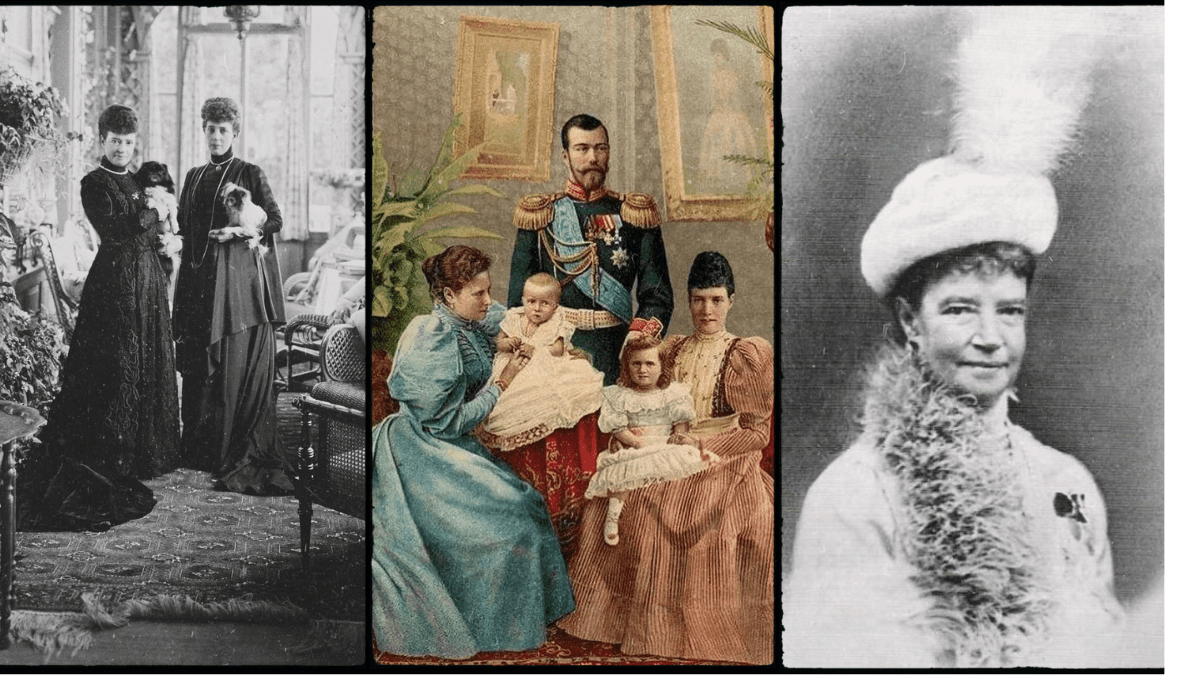

Left: Marie Feodorovna with her sister, Queen Alexandra; Center: with Nicholas II and Alexandra and their daughters, Olga and Tatiana; right: Marie Feodorovna in her later years.

Tension Mounts Between Marie Feodorovna and Empress Alexandra

Marie Feodorovna ruled once again supreme at the heart Saint Petersburg’s glittering society, and comparisons between her innate social finesse and her daughter-in-law’s painful lack of it were a constant topic amongst society gossips.

As the years passed, Nicholas and Alexandra retreated further from St. Petersburg, particularly after their son Alexis was diagnosed with hemophilia. They made their home in the suburban Alexander Palace, doing everything they could to hide the tsarevich’s fatal illness from the public. It was here that Nicholas and Alexandra received frequent visitors from the infamous Grigory Rasputin, who was the only person who could bring relief to Alexis during his frequent hemorrhages.

Marie Feodorovna with Nicholas II and his four daughters.

Nicholas II remained close with his mother, writing to her often, and they consoled one another in the aftermath of an other family crisis in 1912. Marie Feodorovna’s youngest son, Michael, second in line to the throne after the fragile Alexis, married his longtime lover, Natalia Wulfurt, a twice-divorced commoner, and mother of Michael’s only child, George, who was born in 1909.

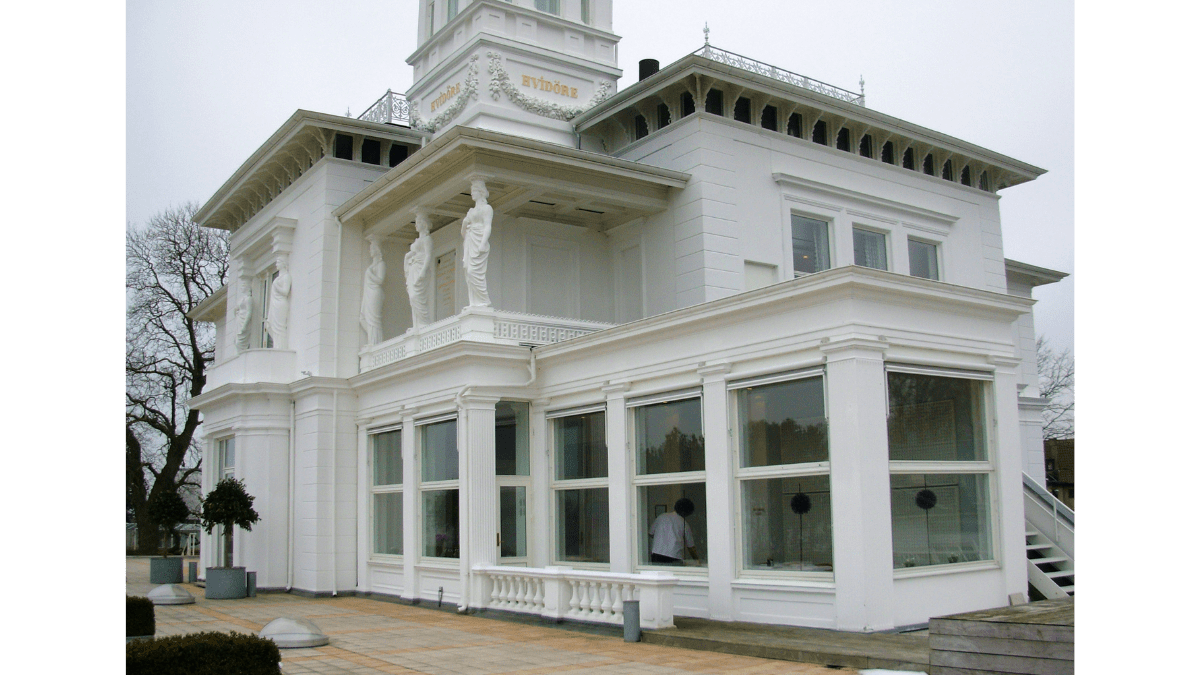

Marie Feodorovna continued to seek consolation in traveling, joining her sister, Dowager Queen Alexandra, each autumn at Hvidore, a house in their native Denmark the sisters purchased in 1906.

Hvidore

Want More Romanov Reading?

Enter your email address below to get instant access to my extensive reading lists about Russian History and the Romanovs.

An Empress at War

In 1914, Russia woefully under-prepared declared war on Germany, setting the stage for the demise of the dynasty. In 1916, Rasputin was assasinated by Marie Feodorovna’s nephew, Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich and Felix Yussupov, the husband of the empress’s granddaughter, Irina.

Marie Feodorovna spent much of the war in Kyiv, where she received the devastating news in 1917 that Nicholas II had abdicated on behalf of himself and his son Alexis, in favor of Grand Duke Michael. Marie Feodorovna hurried to Mogilev to join Nicholas, where they learned that Michael had himself renounced the throne, signaling the end of 304 years of Romanov rule in Russia. Marie Feodorovna returned to Kyiv on her train.

She would never see either son again.

In early April 1919, Marie Feodorovna, accompanied by her two daughters, Grand Duchesses Xenia and Olga and their families, and her household, left Kiev for the Crimea. In April 1919, as the Red Army pushed closer to the Crimea, the British Government, badgered by Queen Alexandra, ordered HMS Marlborough to evacuate the Dowager Empress and her family. Marie Feodorovna refused to leave unless the Marlborough ferried all of the Russian refugees, who were desperate to leave. Captain Charles Johnson wavered, but finally relented, and only after all the refugees and their belongings had been loaded would Marie Feodorovna agree to board.

As HMS Marlborough steamed out of the harbor, another British ship, carrying officers of the Imperial Guard en route to Sevastopol, passed the Marlborough, where Marie Feodorovna stood on the quarterdeck. Across the water came the strains of the Russian Imperial Anthem, sung by the officers in tribute to their beloved empress. It was the last time the Anthem would be heard in its native land.

Marie Feodorvona initially settled in England, where she lived with Queen Alexandra at Marlborough House, but later resettled in her native Denmark. To her dying day, she refused to believe the increasing evidence that Nicholas and his family had been killed in Ekaterinburg, or that Michael had met his end in Perm. She acknowledged no successor to her son, and refused to meet any of the claimants, purporting to be her granddaughter Anastasia.

Marie Feodorovna died in 1928, and the tattered remains of Russian nobility joined European royalty gathered to bid farewell to the last remaining link with Imperial Russia. Her remains were interred in Roskilde Cathedral, the traditional resting place of the Danish Royal Family, but in 2006, her coffin was returned to Russia, via the same route the Sea King’s Daughter had taken 140 years earlier, and she was laid to rest beside her husband, Alexander III in the Peter and Paul Fortress.

An Empress in Exile: Marie Feodorovna’s Final Years

Other Romanov Links Around my Website

- Podcast Interview with Corynne Hall about Queen Victoria and the Romanovs.

- Podcast Interview with C.W. Gortner about his novel, Romanov Empress: A Novel of Tsarina Maria Feodorovna

- Ekaterinburg’s Grisly Centenary: The Final Fate of the Romanovs.

- Long Live the Imperials!

- Have Personality Disorder, Will Rule Russia

Further Reading:

The best book about Marie Feodorovna is Little Mother of Russia by Corynne Hall, but Marie gets lots of coverage in the admirable work of historian Julia Gelardi, From Splendor to Revolution. Marie is a major character in the critically acclaimed television series about Edward VII, Edward the King. In it, Marie is portrayed very well by Jane Lapotaire, who captures Marie’s charm and ebullience, as well as her clear-sighted understanding of the troubles that are coming.

Thank you for stopping by and I hope you’ve enjoyed pursuing this article! There are plenty more to enjoy — check out the list below!

I am a food and travel writer as well as a cruise ship lecturer: my passion is exploring the cuisine, history, and culture of new places and writing about them here.

I hope you’ll consider staying connected with me by subscribing to receive my newsletter and joining the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest!

Join my Newsletter Community

Twice monthly, I’ll send you a digest of my latest articles and posts, travel and food news, and exclusive recommendations you won’t find anywhere else!