Travel to Budapest, Hungary

Budapest’s Iconic Hungarian Parliament

Budapest’s most recognizable landmark is also the country’s tangible symbol of national identity.

Budapest’s Iconic Parliament

Budapest’s Parliament building is a must for visitors to the capital, and indeed, it is hard to miss the flamboyant Neo-Gothic silhouette, the 365 soaring towers and the imposing dome, spread out along the Embankment where the Chain Bridge links the two cities of Buda and Pest. The Országház or “House of Nations” is the third-largest parliament building in the world. Despite impressive growth since the Republic of Hungary was established in 1988, no building in Hungary is larger than the sprawling Parliament, which covers 5,091,329 square feet (473,000 cubic meters), and only neighboring St. Stephen’s Basilica is as tall: both buildings are 96 meters high (316 feet).

What is the Hungarian Diet?

Everything about the Parliament building in Budapest is carefully calculated. Conceived and built as a passionate response to over four centuries of Hungarian yearning for national identity, the Parliament embodies the cherished Hungarian dream of independence from Ottoman, and later Hapsburg rule. Hard-won partial autonomy in the nineteenth century created an urgent need for a building to house the Hungarian Diet. This loose body met in the open air for centuries in modern-day Bratislava, speaking Latin, since Hungarian did not have words for political concepts until the nineteenth century.

The facade of Budapest’s Parliament Building from the Danube River

Building “The Motherland’s House” in Hungary

Hungary’s beloved poet Mihaly Vorosmarty spoke for the nation when he lamented that, “The Motherland does not have a house.” Hungary’s leaders decided to address the problem.

In preparation for the 1000th anniversary of the founding of the Hungarian kingdom by Chief Árpád in 896 CE, a national contest was held to design a Parliament building to preside over the Pest side, proudly facing royal Buda, that bastion of Hapsburg rule. The only stipulation the judges made was that the style could not be Greek revival, the dominating motif in Imperial Vienna.

The Spirit of Hungarian National Identity

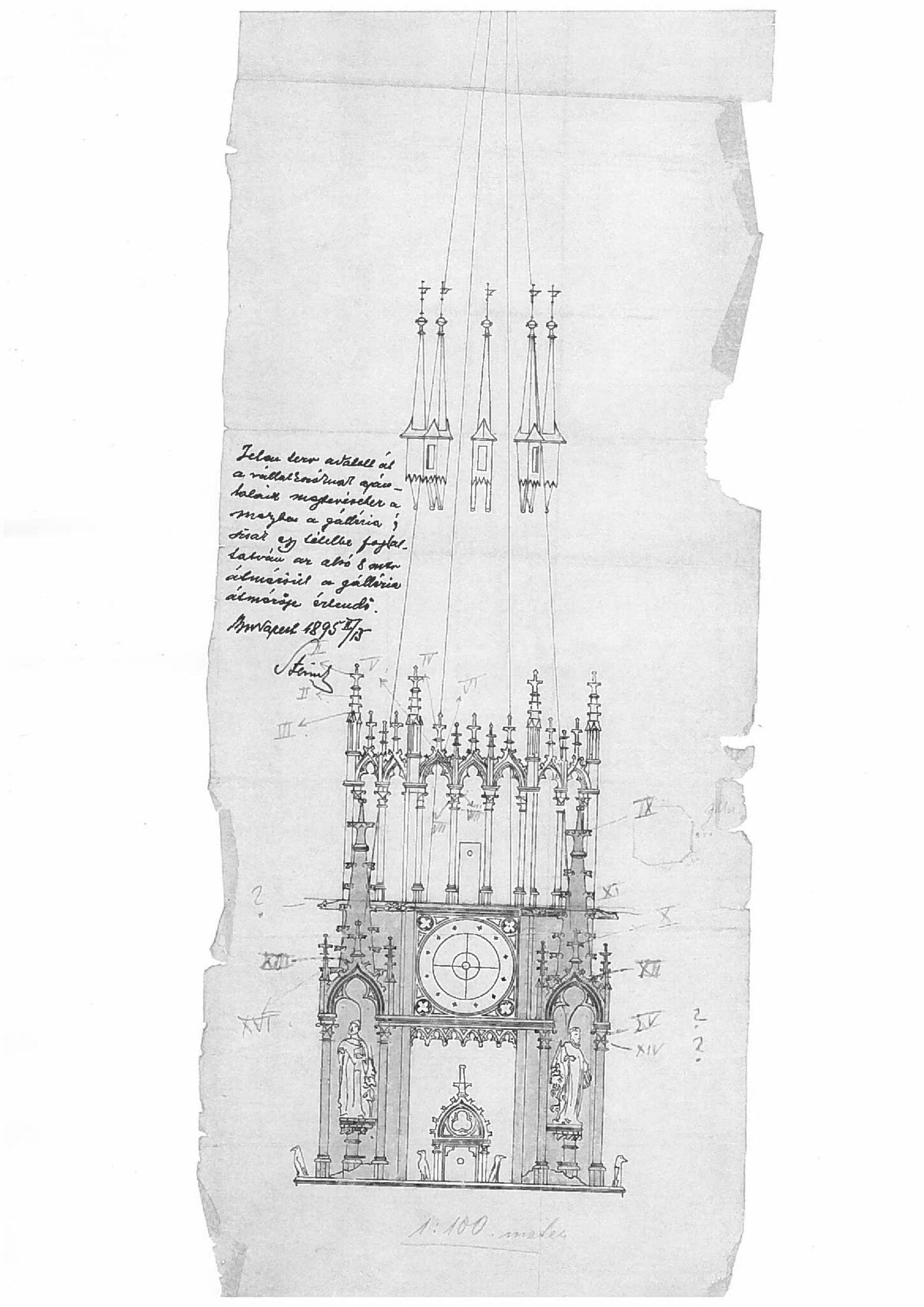

Architect Imre Steindl

Finding no spirit of Hungarian national identity in the stone buildings of the country, architect Imre Steindl turned instead to the grandeur of Neo Gothic design, inspired, no doubt, by the Houses of Parliament in London, built half a century earlier, but also by the Gothic spires of Catholic St. Matthew’s Church dominating the Buda skyline.

“This splendid style,” he later wrote, “of the Middle Ages evokes in the most beautiful way the connection between the natural and spiritual worlds with its perfect beauty, raising enthusiasm, and with its…form soaring through the heights.”

Steindel was awarded the contract and construction began in 1885. No expense was spared and care was taken to employ Hungarian workers, contract with Hungarian suppliers, and wherever possible, to use Hungarian supplies. This national labor of love would take two decades to complete and use over 40 kilos of gold, half a million precious stones, and cost Steindel his eyesight. The finished product, which boasts 365 Gothic turrets — one for each day of the year — and 88 statues, with those of the proud Hungarian kings and rulers facing the Danube, evoked as much euphoria as it did scorn: some finding the vast, opulently decorated interiors gaudy and a hideous drain on the national coffers.

Architect Imre Steindl’s designs for the Parliament

The Parliament Survives Hungary’s Turbulent 20th Century

The twentieth century tested the mettle of the new national symbol. Hungary’s much-depleted territory following World War I meant far fewer delegates to the House. World War II dealt even harsher blows as the retreating Nazi occupying army blew up the Chain Bridge, causing lateral damage to the central dome. Somehow the citizens found the strength, motivation, and materials in those horrible days to repair the Dome. Parliamentarians also managed to smuggle the precious crown of St. Stephen and his royal insignia to the American Army in the face of the advancing Soviet Army. It was taken to Fort Knox for safekeeping and returned to Hungary by President Jimmy Carter in 1978; today these crown jewels are once again on display in the Parliament building.

The Crown Jewels of Hungary returned to the Parliament Building in 1978

Visiting Budapest’s Parliament Today

Independence and membership in the European Union have meant more changes for the Parliament, mostly internal as MPs were given more office space, but also external as visitors to the capital can attest: the soft limestone of the iconic facade is in frequent need of cleaning, possible only with extensive scaffolding. Gradual replacement of a harder, more durable limestone is ongoing.

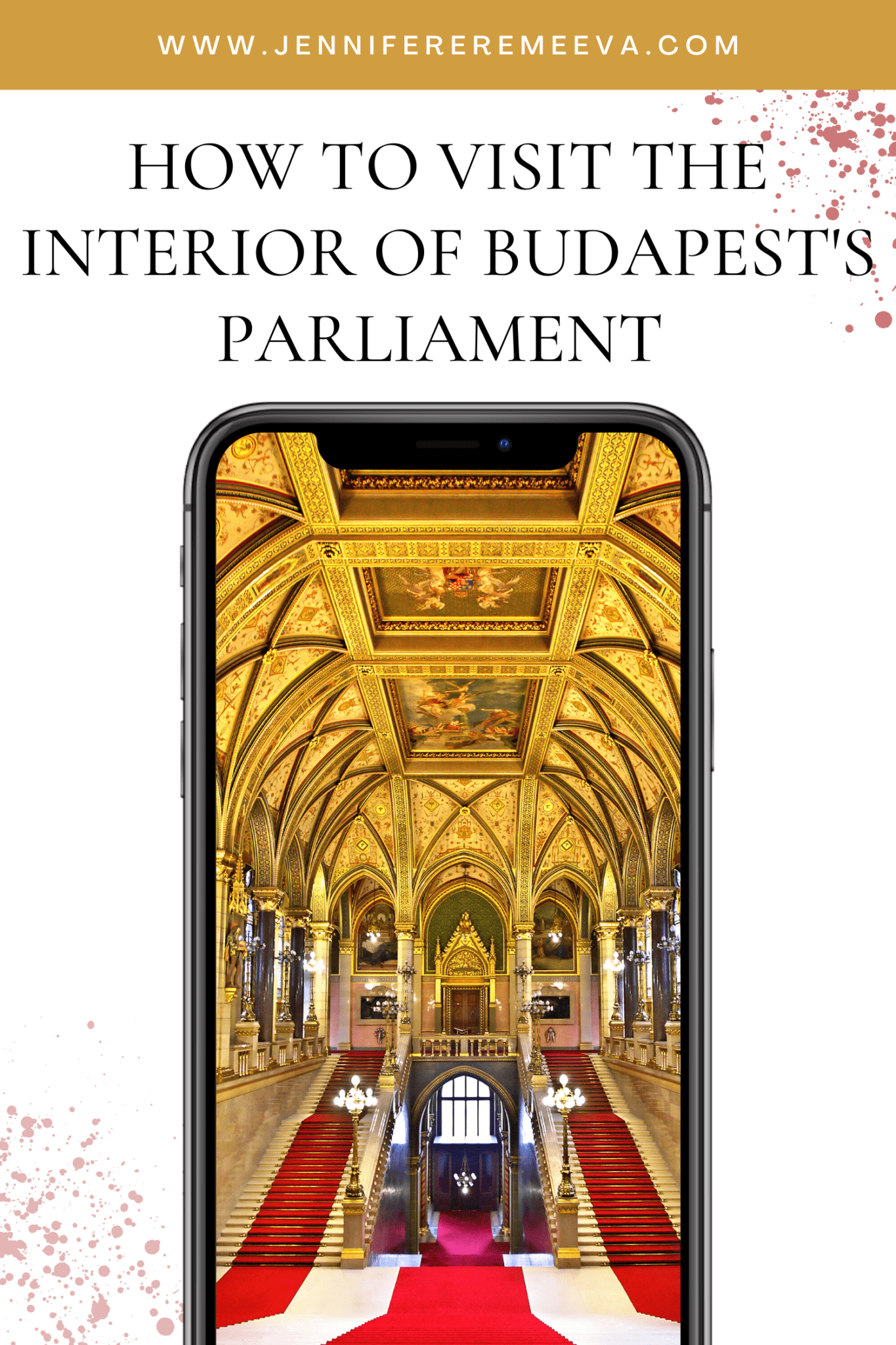

The best-known views of the Parliament building are of its back, or riverside facade ideally enjoyed from the vantage point of a boat on the Danube. But the inside, with its lavish and sumptuous interiors, imposing staircases (over 21 kilometers of stairs), massive frescos recounting the history of the country, and 88 statues of prominent Hungarian rulers are equally impressive. The building continues to serve the purpose for which it was built more than a century ago: to be the tangible symbol of a proud and independent Hungary, and to celebrate the country’s unique heritage, culture, and identity. Long may it stand!

The Stately Grand Staircase inside the Parliament Building in Budapest

Practical Information

Jennifer Recommends: Visit the Interior of the Parliament Building

The Visitor’s Center of the Budapest Parliament Building

Pin this Article!