Russian History

Ekaterinburg’s Grisly Centenary: The Final Fate of the Romanovs

One hundred years ago, Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia, was murdered in Ekaterinburg with his wife, their son and four daughters, and four faithful retainers. This final fate of the Romanovs is considered the “original sin” of the Russian Revolution, and Russia is still atoning for it.

Citizen Romanov

In 1918, Nicholas II, the last of the Romanov Tsars could count the number of times he had traveled beyond the Ural Mountains on one of his hands and still have fingers left to spare. As heir to the throne, Nicholas had acted as honorary chairman of the committee in charge of the construction of the Trans-Siberian railway. In 1891 on his way home from a world tour, Nicholas laid the world’s longest railway’s cornerstone in Vladivostok, but it was only after his abdication in 1917 that the former Tsar of all the Russias spent any significant time in his empire’s eastern territories.

The Imperial Family’s arrival in Ekaterinburg in April 1918 marked the terminus of a months-long journey the former Tsar, his family, and a handful of faithful retainers had made into Russia’s interior. It would also mark the end of their life’s journey. It was in Ekaterinburg that Russia’s last imperial family— Nicholas, his wife Alexandra, their youngest child, the hemophiliac Tsarevich Alexei, and their four daughters, the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia, met a grisly end at the hands of the Bolsheviks. It has been one hundred years since this “original sin” of the Russian Revolution was committed, making Nicholas II and his family Holy Martyrs and Ekaterinburg a synonym for Golgotha amongst the growing number of devotees of Russia’s last Imperial Family.

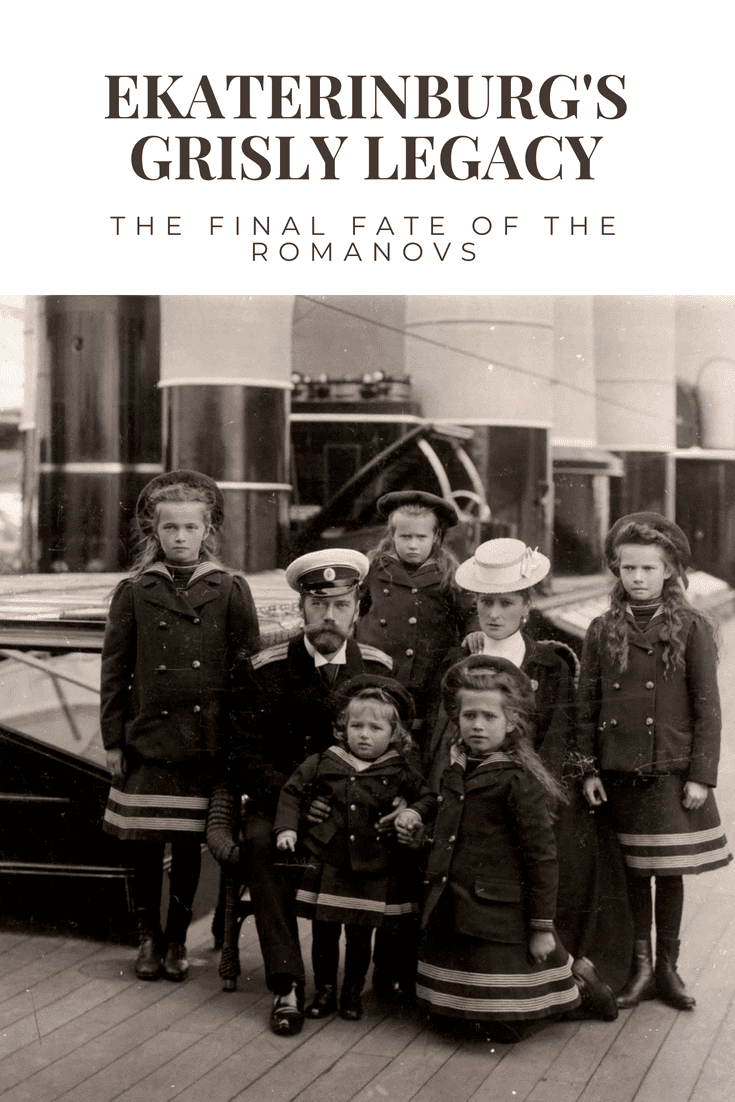

Nicholas and Alexandra and their Children on the Imperial Yacht The Standart– By Published by Rotary Photographic Co Ltd. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

War, Revolution, and Abdication

Ekaterinburg was not a planned stop on the Imperial Family’s journey east, but by 1918, they were accustomed to events overtaking them. Nicholas’s stubborn refusal to introduce much-needed reforms and the representational government had brought his empire to the brink of revolution in 1905. The ensuing truce between autocrat and people had been an uneasy one, but it lasted until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. War stretched Russia’s economy, overburdened military, and antiquated infrastructure to the breaking point. In February of 1917, bread riots and workers strikes erupted in Petrograd, in the first of that year’s two revolutions. Members of the new Provisional Government caught up with Nicholas on his way from Army Headquarters and persuaded him to abdicate. The 304-year dynasty, which had begun with the election of Mikhail Romanov in 1613 at the Ipatiev Monastery, ended in a railway car near Pskov.

House Arrest in Tsarskoye Selo

The family was initially confined at home in the Alexander Palace in suburban Tsarskoye Selo where they planted a vegetable garden and chopped firewood while they waited for the Provisional Government to decide their fate. Britain was approached — King George V and Nicholas were first cousins— but George demurred, unwilling to risk acerbating growing anti-monarchical sentiment in Britain, then dominated by the Labor Government. Kaiser Wilhelm II offered safe passage to Germany, but the Romanovs refused even to consider it, even though Alexandra and Wilhelm were first cousins.

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia with members of his family in the private grounds of Tsarskoe Selo. — Source: Maria Fyodorovna’s Album: [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

East to Tobolsk

Throughout the summer of 1917, as clashes between the Bolsheviks and the Provisional Government increased, with the latter steadily losing control, Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky decided to send the Romanovs into the interior of the country for their own safety from the Petrograd mob and the Bolsheviks. He justified this in his memoirs as also the most expedient way to arrange for them to leave Russia via the Far East. For the immediate future, Kerensky chose Tobolsk, a sleepy river town far away from the railway line that became inaccessible during the Siberian winter.

The Romanovs spent the autumn and winter quietly in marked contrast to events in Petrograd, where Lenin’s Bolsheviks wrested power from the Provisional Government in a coup d’état in October. If Russia had been chaotic before, now it verged on anarchy. A bloody civil war now ensued, pitting the ragtag Red Army against the counter-revolutionary White Army. The most disciplined, and arguably successful of these was commanded by Admiral Kolchak, who enlisted the assistance of a force of Czech soldiers and the support of Allied Governments. Kolchak and his forces worked their way west from Vladivostok, winning victories and garnering support as they did.

Nicholas II and children in Tobolsk. By Romanov family or retinue [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Ekaterinburg

Kolchak’s steady march west worried the Bolsheviks, who planned a very public show trial of the former Tsar in Moscow as justification for the Revolution. In the early spring of 1918, they dispatched an armed detachment under the command of V.V. Yakovlev to Tobolsk to bring the Romanovs to Moscow. They arrived to find Tsarevich Alexei in the throes of a severe hemorrhage and unable to travel. The family separated: Nicholas, Alexandra, and Grand Duchess Maria accompanied Yakovlev, while Olga, Tatiana, and Anastasia, their tutors and servants remained behind to nurse Alexei.

Yakovlev did his best to bypass Ekaterinburg, where loyalty to the Bolsheviks and fervor for the revolution had found loyal supporters amongst the miners and metal factory workers. Yakovlev knew that the Ekaterinburg Ural Regional Soviet was desperate to get its hands on the imperial prisoners. His fears were well founded when his party was overcome by troops who took the family into custody.

Nicholas, Alexandra, and Maria were brought to the home of N. Ipatiev, a prosperous Ekaterinburg merchant where a large fence had been erected to keep the prisoners in and curious townsfolk out. Three weeks later, Alexei and his sisters traveled to join them by steamer and train. At Ekaterinburg, however, the children’s’ foreign tutors and most of the entourage who had accompanied the Romanovs into exile was not allowed to proceed with the family, only Dr. Botkin, Anna Demidova, Alexey Trupp, and Ivan Kharitonov, the cook.

Life in the Ipatiev house that spring and early summer was monotonous. Alexandra and Alexei were often ill, Olga descended into a bout of melancholia, and Nicholas found himself driven to distraction from lack of exercise. The profoundly religious Romanovs were not allowed to attend church services and felt the deprivation keenly. Only whispered hints of possible rescue kept their spirits from flagging. Ekaterinburg teemed with would-be saviors of the monarchy, but with a few exceptions most were either fanatics or well-intentioned but were ill-equipped to attempt a rescue of the most famous family in Russia, which included two invalids and five women.

A Race Against Time

Kolchak remained their best hope, but his advance towards Ekaterinburg intensified the urgency to deal with the Imperial Family one way or another. In early July, Yaakov Yurovsky took over as Commandant of the Ipatiev House with a mandate—possibly from Lenin himself — to kill the Imperial Family. Yurovsky put his plans in motion on the night of July 17. Under the pretext of moving the family away from the advancing White Army, Yurovsky had them dress and line up, as if for a photograph, in the basement of the Ipatiev House. He announced to the assembled group of eleven that given the fact that the Romanov relatives continued to attack Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee had decided to execute them.

There was barely time to react before the 12-man squad began to open fire. Nicholas, Alexandra, Dr. Botkin, Trupp, and Kharitonov died quickly, but Alexei and his sisters did not; Anastasia had to be bayonetted to death. How the hemophiliac Tsarevich survived the repeated onslaught of bullets remains a mystery, but the assailants discovered the reason the Grand Duchesses proved hardest to kill when they stripped the clothes from them and found corsets into which the family had carefully sewn precious jewels.

July 17, 1918

Yurovsky now raced against time to dispose of the bodies. Hampered by a punch-drunk crew and a truck that kept getting stuck in the mud, he first threw the eleven corpses down an abandoned mineshaft, tossing in hand grenades for good measure. Later, he returned to dredge up the bodies with the intention of throwing them down a much deeper shaft but was forced to bury them when his truck was once more mired in mud. Yurovsky ordered that the faces of the victims be obliterated by acid so they could not be recognized, and for good measure, he dragged the bodies of Alexei and Marie to a separate hole to create confusion over the number of corpses should the advancing White Army excavate the grave site.

The Bolsheviks sowed further confusion by announcing the death of Nicholas II. Alexei and Alexandra, it was suggested, had been taken to an undisclosed location for safekeeping. The fate of the Grand Duchesses was left ambiguous, which opened the way for numerous pretenders throughout the twenties, including the famous Anna Anderson, who spent a lifetime trying to prove that she was Anastasia. Bones found in 1979 in the central grave hole in the woods outside Ekaterinburg by an amateur sleuth were subjected to DNA testing in the 1990s and subsequently buried in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg. The remains of Marie and Alexei await a final go-ahead by the Holy Synod.

Atoning for the Original Sin of the Russian Revolution

Ekaterinburg has done its best to do penance for the “original sin” of the Russian Revolution. The Ipatiev House was pulled down in 1975, a project overseen by a young party official named Boris Yeltsin.

Twenty-three years later, as Russia’s first President, Yeltsin would stand unsteadily in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg to watch the internment of bones found in the primary grave outside Ekaterinburg in a chapel dedicated to the Last Imperial Family and their four faithful servants. All eleven are now Holy Martyrs of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The proposed bones of Marie and Alexei from the smaller grave still await final approval by the Holy Synod for internment

In place of the Ipatiev House stands the richly decorated Church on the Blood in Honour of All Saints Resplendent in the Russian Lands and where the bones of the Romanovs once lay is now the site of the Monastery of the Holy Tsarist Passion-Bearers.

Both are inundated with worshippers, particularly in July when tens of thousands of Orthodox Faithful take part in the “Tsar Days” in remembrance of the death of Nicholas II, his family, and their servants.

Notes from the Author:

Thank you for stopping by to read this post. I always welcome comments and emails from readers. For more images of the Romanovs throughout the ages, please do visit my Romanov Dynasty Pinterest Board.

Please note that a shorter version of this post was first published in The Moscow Times’s print edition and City Guide to Ekaterinburg on June 1, 2018. A link to that version may be found here.

This site does contain affiliate links. Clicking the links provided here does not obligate you to buy any product, but any purchases you do make will net me a small commission which helps to support the work I do as a freelance writer and author. I do not recommend items I do not personally endorse and I stand by all my recommendations.

Because of the subject of this post, I feel it is important to note that I sincerely believe that Nicholas II and his family were all killed in the basement of the Ipatiev House on the night of July 17-18, 1918. I do not believe that any of the family were able to escape their tragic fate.

Pin this Article

I’m totally fascinated with the Romanov Family. I have devoured every bit of information I can read.

They are endlessly fascinating for sure! May I ask what your favorite book has been as you’ve explored them?