Iceland’s culinary history is an example of human ingenuity and resilience on a remote island in the face of extreme environmental conditions. From the early Viking settlers to today’s innovative chefs, Icelandic cuisine has developed by making much out of comparatively in a variety of ways to source, store, and prepare food. The must-try of things to eat and drink in Iceland gets longer each year!

This post contains affiliate links, including links from the Amazon Associates programs. These links will direct you to products I recommend for further exploration and enjoyment of the topics I cover on my website and in my lectures. See more in the Privacy Policy below.

Although I worked for several years in the food writing space, my expectations about Iceland’s local cuisine were low when I first visited the country in 2015 for the wonderful Iceland Writers Retreat, which I attended for numerous years and do highly recommend. How delightful to be proved so wrong about a country’s cuisine. I came a few days before the conference to explore and get some writing done, and almost immediately I fell in love with tastes of Iceland, a love that has proved enduring for many subsequent visits.

The culinary scene in Iceland has expanded and grown — each time I visit I’m struck by the number of new local restaurants, ice cream parlors, and coffee shops and by how difficult it is to get a table in Reykjavik’s eateries (reservations are essential!) I’ve sampled all kinds of local food from a bowl of incomparable lobster soup at the very simple Seabaron to a high end meal at trendy DILL, and almost everything in between, I have not had a bad meal in Iceland!

Exploring this remarkable country through its culinary lens is a unique experience and a great way to get under the skin of Iceland, and in this article I’ve included some guided tours lead by a knowledgeable local guide to help you learn more about the country’s innovative food producers, restauranteurs, brewers and distillers, and those who continue to take Iceland’s cuisine to new heights.

Smoked Lamb | Photo credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

Iceland’s Culinary History

Early Settlement and Viking Influence

When the Vikings settled Iceland in the 9th century, the only mammal on the island was the Arctic fox. The Norse settlers brought livestock such as sheep, cattle, and pigs to Iceland, as well as the culinary traditions from the Viking homelands. Celtic slaves (primarily women) brought other culinary traditions, such incorporating nutrient-dense dulse (seaweed) as a flavoring and preservative, which added much needed iron, minerals, fiber, and antioxidants to the medieval Icelandic diet.

The story of Flóki Vilgerðarson, one of the first settlers to come to Iceland deliberately in the 9th century, illustrates the challenges faced by early settlers. According to the Book of Settlement, Flóki tried to settle in the West Fjords but was ill-prepared for the harsh winter. Having failed to provision enough fodder, he lost all his livestock and, upon seeing the fjord Ísafjörður full of ice, named the entire land “Iceland.” This tale points to the key challenge of scarcity that would shape Icelandic cuisine for centuries to come: it would prove hard to convince settlers to come to a place called “Iceland.” This is probably why Erik the Red dubbed the land he found to the west of Iceland, “Greenland” — a far more appealing prospect.

Abraham Ortelius Islandia c.1590 | via Wikimedia Commons

Adapting to the Harsh Environment

The early Icelanders faced several challenges in food production and preservation. Although the island had pine and birch trees, the settlers cleared the forests to build and heat their houses, as well as create fields to plant some hearty grains, root vegetables, and pastureland. This practice led to significant soil erosion and further shaped the development of Icelandic cuisine.

Fuel became scarce, so boiling became the most common cooking method, using fires made from peat or dried sheep manure. The scarcity of salt, crucial for food preservation but difficult to produce locally, led Icelanders to attempt innovative methods like freezing seawater to concentrate salt. This met with limited success, and salt remained an important and expensive import from Scandinavia.

The cold climate made it difficult to grow grains, resulting in a diet heavily reliant on meat and fish. Icelanders developed unique preservation methods. Fish and meat were air-dried in the cool air, with dried cod becoming a major export and a staple food. Where wood was available, smoking was used to preserve meat and fish. Fermentation also played a crucial role, with whey, a byproduct of cheese and skyr production, being used to preserve meat in large barrels dug into kitchen floors.

Interior of a Settlement Era Dwelling in Iceland’s National Museum | Photo Credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

The Importance of Dairy

Dairy products played a crucial role in Icelandic cuisine. The settlers brought cheese-making expertise from Norway, and butter became so important it was used as a commodity to calculate rent and taxes. Skyr, a type of yogurt-like cheese, became a staple food thanks to its high protein content and long shelf life. It is still popular in Iceland today.

Many Icelanders turned to geothermal springs for cooking, a practice documented as early as 1199. Food would be placed in a cauldron and lowered into boiling water. This method gave rise to dishes like hverabrauð or “hot spring bread,” a moist rye bread steamed in a container for 24 hours using geothermal heat. You can still find hverabrauð today, which is delicious!

Cooking pots were expensive and often had to be imported, as there was no suitable clay in Iceland for pottery. This scarcity led to unusual practices, such as the use of baptismal fonts as cauldrons, a practice so common that in 1345, the Bishop of Skalholt had to issue a ban on using them for cooking soups and stews.

Geysir Bread | Photo Credit: Shutterstock

The Middle Ages and Foreign Influence

The 15th century, known as “The English Century,” when English merchants and fishermen came to Iceland for its abundant cod and wool. This brought grain, utensils, wood, and other goods to Iceland. This period saw the emergence of a small wealthy class of Icelandic landowners who could afford to import luxury foods from Europe.

However, most Icelanders continued to struggle with poverty and food scarcity. The eruption of the volcano Hekla in 1389, followed by a severe winter and floods, and then the Black Death, further exacerbated these challenges. In 1397, Iceland came under Danish rule, which would significantly influence its cuisine in the coming centuries.

The Age of Enlightenment and 19th Century

The 18th century brought changes to Iceland as scientists introduced new methods of growing food and cooking. In 1754, King Christian V of Denmark decreed Icelandic farmers must set aside land to plant vegetables. Despite initial resistance, this eventually led to the introduction of new crops, most notably potatoes and other root vegetables, which became widespread by the turn of the century.

Danish cuisine became the dominant influence during this period. Danish culinary traditions heavily influenced the first Icelandic cookbooks, such as “A Simple Cookery Notebook for Gentlewomen” published in 1800,. These early cookbooks provide insight into the diet of wealthy Icelanders but tell us little about the food of the lower classes.

The publication of “The Women’s Education” by Elin Briem in 1858 marked a significant milestone as the first truly Icelandic cookbook. Briem, who ran one of Iceland’s first homemaker schools, helped codify and preserve traditional Icelandic recipes.

20th Century: Modernization and Global Influences

The turn of the 20th century brought significant changes to Icelandic cuisine. Introducing ovens and stoves led to a baking boom, leading to a rise in the popularity of traditional Scandinavian cakes and pastries, which has never dissipated. World Wars I and II brought isolation but also new culinary influences from British and American troops, including tinned food and fish and chips.

Fish and Chips have become wildly popular in Iceland | Photo Credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

“Matur og Drykkur” (Food and Drink)

One of the most influential cookbooks in Icelandic culinary history is “Matur og Drykkur” (Food and Drink), first published in 1947 by Helga Sigurðardóttir. This comprehensive cookbook became a staple in Icelandic households, playing a crucial role in preserving traditional recipes and cooking methods. It served as a bridge between old and new culinary practices, helping Icelanders maintain their food heritage while adapting to modern kitchen technologies. The book’s enduring popularity, with multiple reprints and updates over the decades, reflects its significance in shaping Icelandic home cooking. “Matur og Drykkur” not only standardized many classic Icelandic recipes but also introduced new dishes, contributing to the evolution of Icelandic cuisine in the 20th century.

The post-war period saw an increasing appetite for foreign foods and flavors. The 1960s and 1970s saw the introduction of dishes like breaded and fried cutlets, hamburgers, and pasta. Salads became popular, often featuring mayonnaise-heavy preparations or canned fruits. The Icelandic Dairy Produce Marketing Association actively promoted new cheese-based recipes, leading to the popularity of seafood gratins.

By the 1980s, there was a dramatic transformation of the restaurant scene. People started eating out more frequently, enjoying foreign cuisines such as Italian, Chinese, American, and Indian. There was also an increased interest in nutrition and healthy diets, alongside a fast food boom.

Financial Boom, Bust, and Culinary Renaissance

The financial boom of 2004-2008 saw an influx of exotic ingredients and international culinary trends in Iceland. However, the subsequent financial crash in October 2008 led to a period of austerity and a return to culinary roots.

This economic downturn, paradoxically, sparked a culinary renaissance as Icelandic chefs turned their attention back to native resources and traditional cuisine, combining old methods with new techniques. This fusion approach has proved wildly popular, showcasing local game, fowl, and simple but delicious fish dishes.

The “Pots and Pans Revolution” following the financial crisis also impacted Iceland’s food culture. As Icelanders demanded political and economic reforms, there was a renewed interest in local, sustainable food production and traditional Icelandic ingredients.

Modern Icelandic Cuisine: Innovation Meets Tradition

Today, Iceland is experiencing a culinary renaissance: chefs tweak traditional dishes and methods with modern techniques. Chefs are rediscovering and reimagining traditional preservation methods like drying, smoking, and fermenting. There’s a renewed appreciation for ingredients like dried fish (hardfiskur), smoked lamb (hangikjöt), and even fermented shark (hákarl) and a return to cooking in the traditional way. Iceland has become a major gastronomic hub, with new restaurants cropping up not only in major cities such as Reykjavik and Akyueri but all around the perimeter of Iceland, which is becoming an increasingly popular road trip for visitors who want to take in all the beauty of this island nation. Typical ingredients on Icelandic menus include arctic char and other Icelandic fish, shark meat, whale meat, sheep’s head, lamb meat, puffin meat, minke whale, and Icelandic skyr.

Innovative practices in agriculture and aquaculture have also shaped modern Icelandic cuisine. Geothermal greenhouses allow for year-round vegetable production, while sustainable fishing practices ensure the continued abundance of seafood.

Exploring Iceland’s Culinary Landscape

Reykjavik

- Private Food Walking Tour in Reykjavik

- Private Reykjavik Folklore and Food Walking Tour

- Funky Food & Beer Walk of Reykjavik – Traditional food and history

- Reykjavik’s Finest Catch: Guided Sea Angling Tour for All Levels

- Reykjavik Food Tour – Old Harbor Walking Tour

- Reykjavik Food & Wine Tour

- Reykjavik Food Tour – Supermarket Tour & Lunch at Microbrewery

- Reykjavik Food Walk – Local Foodie Adventure in Iceland

- Reykjavik Food Lovers Tour – Icelandic Traditional Food

- Golden Circle, Fridheimar Farm & Horses Small Group Tour from Reykjavik

- Reykjavik Beer & Booze Tour

- Weekend Reykjavik Food Tour with a stop at the Reykjavik Flea Market

Akuyeri

Iceland’s Culinary Highlights

Modern Salt-Making in Iceland

The revival of traditional salt-making techniques in Iceland using geothermal energy is a superb example of how the country is blending its unique natural resources with culinary traditions. This modern approach to salt production not only produces high-quality sea salt but also does so in an environmentally friendly manner.

Saltverk, a company based in the Westfjords of Iceland, has been at the forefront of this revival. They produce flaky sea salt using a method that dates back to the 17th century, but with a modern, sustainable twist. The process begins with seawater from the pristine Westfjords, which is then slowly heated using geothermal energy from hot springs in the area.

Saltverk salts in Iceland | Photo credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

Using geothermal energy in this process sets Icelandic salt-making apart. It allows for a slow evaporation process that results in delicate, flaky salt crystals with no environmental impact. This method is not only sustainable but also produces salt with a unique flavor profile that reflects the purity of Iceland’s marine environment.

Saltverk produces various flavored salts as well, incorporating local ingredients like Arctic thyme, licorice, rhubarb, lava, and birch smoked salt. These products have gained international recognition, being used by top chefs around the world and winning awards for their quality and sustainability.

This revival of salt-making in Iceland is more than just a culinary trend; it’s a testament to Iceland’s commitment to sustainable practices and the innovative use of its natural resources. It also represents a return to traditional food production methods, albeit with a modern, eco-friendly approach, further enriching Iceland’s culinary landscape.

You can purchase Saltverk Salts here. Nothing tastes better than the Arctic Thyme salt on a roast chicken!

Blue Mussel Farming

Another innovative example of Iceland’s modern approach to sustainable food production is the burgeoning blue mussel farming industry. Blue mussels, known locally as “kræklingur,” are native to Icelandic waters but have only recently been cultivated on a commercial scale. The cold, clean waters around Iceland provide an ideal environment for mussel farming, resulting in high-quality, flavorful shellfish.

The development of blue mussel farming in Iceland began in the early 2000s, with experimental farms set up in various fjords around the country. The industry has since grown steadily, with farms now operating in several locations, including Breiðafjörður, Eyjafjörður, and Hvalfjörður. These farms use long-line cultivation methods, which have minimal impact on the marine environment and produce mussels of exceptional quality.

Iceland has successfully developed blue mussel farming | Photo Credit: Shutterstock

Icelandic Herring

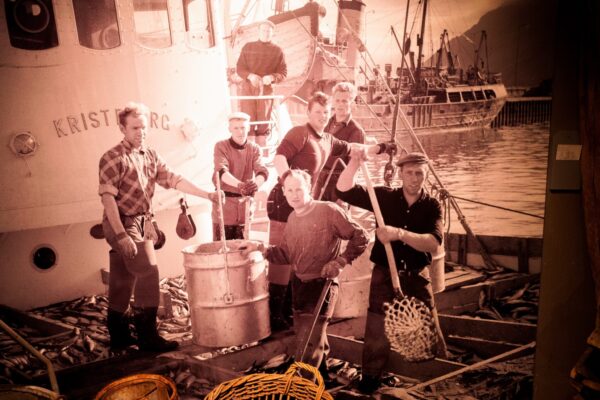

The Icelandic herring industry played a crucial role in the country’s economic development during the 20th century. Known as the “herring adventure” or “herring boom,” this period saw small fishing villages transform into bustling towns as the herring catch brought unprecedented prosperity. The town of Siglufjörður in northern Iceland became the herring capital of the world, with its population swelling during the summer fishing season.

Today, the Herring Era Museum in Siglufjörður offers visitors a fascinating glimpse into this pivotal time in Iceland’s history. The museum, housed in restored buildings from the herring era, features exhibits on fishing techniques, processing methods, and the social impact of the industry. Visitors can explore original fishing boats, and processing facilities, and even experience a reenactment of the busy dockside atmosphere during the herring boom. The museum not only preserves this important part of Iceland’s cultural heritage but also serves as a reminder of the significant impact that a single industry can have on a nation’s development.

Herring Era Museum in Siglufjörður | Photo credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

Iceland’s Growing Craft Beer Industry

The craft beer industry in Iceland has experienced a remarkable evolution in recent years, transforming from a country with strict alcohol regulations to a burgeoning hub for innovative and flavorful brews. This development is noteworthy given Iceland’s history with beer prohibition, which lasted from 1915 to 1989.

Following the legalization of beer, the Icelandic brewing scene initially focused on mass-produced lagers. However, the early 2000s saw the emergence of craft breweries, sparked by a growing interest in diverse beer styles and flavors. Pioneers like Ölvisholt Brugghús and Borg Brugghús paved the way for a craft beer revolution, introducing Icelanders to ales, stouts, and more experimental brews.

Today, Iceland boasts a vibrant craft beer scene with numerous microbreweries scattered across the country. These breweries often draw inspiration from Iceland’s unique environment, incorporating local ingredients like Arctic thyme, birch, and even Icelandic moss into their recipes. Some brewers have even experimented with smoked beers, paying homage to traditional Icelandic food preservation methods.

Ísafjörður’s Dokkan Brugghús | Photo credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

Among the most popular craft beer brands in Iceland are Einstök, known for their White Ale and Arctic Pale Ale, and Borg Brugghús, which offers a diverse range, including the Úlfur IPA and Garún Imperial Stout. Kex Brewing, associated with Reykjavik’s Kex Hostel, has gained recognition for its innovative brews, while Ölvisholt Brugghús’ Lava, a smoked imperial stout, has achieved international acclaim.

Ísafjörður’s Dokkan Brugghús is well worth a visit to try their extensive menu to craft beers and local cheese and sausage. AAddress: Sindragata 4, 400 Iceland.

The growth of the craft beer industry has also influenced Iceland’s drinking culture. Beer festivals, such as the annual Icelandic Beer Festival, have become popular events, attracting both local and international beer enthusiasts. Many bars and restaurants in Reykjavik and other major towns now offer extensive craft beer selections, reflecting the increased demand for diverse and high-quality brews.

As the industry continues to mature, Icelandic craft brewers are gaining recognition on the global stage; several have won acclaim at international beer competitions. This success has not only boosted the local economy but has also added an extra dimension to Iceland’s culinary identity, making craft beer an integral part of the modern Icelandic gastronomic experience.

Explore Iceland’s Craft Beer Industry

Friðheimar Tomato Farm in Reykholt

One of the most fascinating examples of Iceland’s innovative approach to agriculture is the Friðheimar tomato farm in Reykholt. This state-of-the-art greenhouse facility harnesses Iceland’s abundant geothermal energy to grow tomatoes year-round, despite the country’s harsh climate. The farm uses natural hot springs to heat the greenhouses and employs bumblebees for pollination, creating a sustainable ecosystem. Friðheimar produces about 370 tons of tomatoes annually, accounting for a significant portion of Iceland’s tomato consumption. Visitors can tour the facility, to learn about the innovative growing techniques, and even enjoy a meal at the on-site restaurant, where tomatoes feature prominently in every dish, from tomato soup to tomato ice cream. This unique farm not only showcases Iceland’s commitment to sustainable agriculture but also shows how the country’s natural resources can be used creatively to overcome environmental challenges.

Visit the Friðheimar Tomato Farm in Reykholt.

The Friðheimar Restaurant | Photo credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

Classic Icelandic Dishes and Beverages to Try

Iceland’s Famous Hot Dog

No discussion of Icelandic cuisine would be complete without mentioning Reykjavik’s famous hot dog, locally known as “pylsur”. The Bæjarins Beztu Pylsur stand, which translates to “The Best Hot Dog in Town”, has been a culinary landmark in Reykjavik since 1937, and the locals take pride in owning the best hot dogs not only in the Nordic countries but in the entire world! These hot dogs are made primarily from Icelandic lamb, with some pork and beef, giving them a unique flavor profile. They’re typically served “ein með öllu” (with everything), which includes ketchup, sweet mustard, remoulade, crispy fried onions, and raw onions. The combination of flavors and textures has made these hot dogs a favorite among locals and tourists alike, with even international celebrities stopping by for a taste. The popularity of these hot dogs reflects Iceland’s ability to elevate simple street food into a national culinary icon, blending local ingredients with global fast-food culture.

The Bæjarins beztu hot dog stand is on Tryggvagata 1, 101 Reykjavík.

Iceland’s “pylsur” The Best Hot Dog in Town! | Photo Credit: Mayer Chan via Shutterstock

Lobster Soup at The Seabaron (Sægreifinn)

The Seabaron (Sægreifinn) is always my first and last visit when I’m in Reykjavik. It was founded by Kjartan Halldórsson, a former fisherman and coast guard chef, who opened Sægreifinn’s doors in 2003. Kjartan, affectionately known as the Sea Baron, quickly gained fame for his lobster soup, a recipe he perfected over years of cooking at sea. I have had a lot of lobster soup in my time, but nothing comes close to this lobster soup’s rich, flavorful broth combined with generous chunks of langoustine (often referred to as lobster in Iceland). It became an instant hit with locals and tourists alike. The restaurant’s humble beginnings in a small, blue building by the old harbor, its no-frills approach, and the founder’s colorful personality all contribute to its charm. Even after Kjartan’s passing in 2015, the Seabaron has maintained its reputation, continuing to serve the famous lobster soup along with an array of fresh fish skewers, staying true to its founder’s vision of simple, delicious seafood.

Sægreifinn’s Famous Lobster Soup | Photo credit: Jennifer Eremeeva

Note: this is a tiny and simple restaurant with communal tables and benches. Reservations are not required, but during the high season, be prepared to wait for your bowl! It will be worth it!

- Address: Geirsgata 8, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland

- Website: https://www.saegreifinn.is

Icelandic Lamb

Sheep farming has been an integral part of Icelandic culture and economy for over a thousand years, since the 9th century. The Icelandic sheep, descendants of the short-tailed Norse breed brought by the Viking settlers, are well-adapted to the harsh Icelandic climate and have played a crucial role in the country’s survival and culinary traditions.

Icelandic sheep are known for their hardiness and ability to thrive in challenging conditions. During the summer months, they roam freely in the highlands, grazing on diverse vegetation, which contributes to the unique flavor of Icelandic lamb. This free-range grazing practice, known as “réttir,” is an annual event where farmers gather their sheep from the mountains to prepare for the winter months.

Icelandic Sheep | Photo credit: Umomos via Shutterstock

Icelandic lamb is renowned for its tender texture and distinctive taste, often described as delicate and slightly gamey. The meat’s quality is attributed to the sheep’s diet of wild herbs, berries, and grasses, as well as the stress-free environment in which they are raised. Icelandic lamb is leaner compared to lamb from many other countries, making it a healthier option.

In Icelandic cuisine, lamb is a staple ingredient used in various traditional dishes. One of the most popular preparations is “hangikjöt,” or smoked lamb, which is traditionally served during Christmas. The meat is smoked using birch or dried sheep dung, giving it a unique flavor. Other common lamb dishes include “lambakjöt í karrý” (lamb curry), “lambalæri” (roasted leg of lamb), and “kjötsúpa” (meat soup), which often features lamb as the primary meat.

Modern Icelandic chefs are also incorporating lamb into innovative dishes, blending traditional flavors with contemporary culinary techniques. This has led to the creation of dishes like lamb tartare, slow-cooked lamb shanks with Nordic herbs, and lamb sliders with skyr sauce, showcasing the versatility of this cherished ingredient.

The importance of sheep farming extends beyond culinary applications. Wool from Icelandic sheep, known for its warmth and water-resistant properties, is used to create the famous Icelandic sweaters or “lopapeysa.” This further emphasizes the integral role of sheep in Iceland’s cultural and economic landscape.

As Iceland continues to gain recognition as a culinary destination, its lamb remains a point of pride and a testament to the country’s agricultural heritage. The sustainable and ethical practices in Icelandic sheep farming, combined with the unique flavors imparted by the island’s pristine environment, ensure that Icelandic lamb will continue to be a cherished ingredient in both traditional and modern Icelandic cuisine.

Puffin Meat & Eggs

Puffin meat and eggs have been a part of traditional Icelandic cuisine for centuries, particularly in coastal communities where these seabirds are abundant. The Atlantic Puffin, with its distinctive colorful beak, has long been hunted for both its meat and eggs, which were valuable sources of protein in Iceland’s harsh winters.

Puffin meat is dark and rich, often described as having a taste similar to duck or liver, with a slightly fishy undertone. Traditionally, it was smoked, salted, or dried for preservation, and this remains one of the best ways to enjoy this local delicacy. In modern Icelandic cuisine, puffin is sometimes served as a starter, often smoked and paired with a berry sauce to balance its strong flavor. However, it’s important to note that puffin consumption has become controversial in recent years because of conservation concerns, and many restaurants have removed it from their menus.

Puffins in Iceland | Photo credit: LouieLea9 via Shutterstock

Puffin eggs, while less common in modern cuisine, were once a prized delicacy by the Icelandic people. The eggs are larger than chicken eggs, with a creamy yolk and a slightly salty taste. Egg hunting, or “eggjataka,” was a dangerous but important tradition in Iceland. Skilled egg hunters, known as “eggjamaður,” would scale steep cliffs to collect eggs from puffin nests.

These egg hunters employed incredible skill and bravery. They would descend the cliffs on ropes or use long poles with nets attached to collect the eggs. This practice required intimate knowledge of the local landscape and bird behavior. The tradition of egg hunting was not just about food; it was a rite of passage and a way to prove one’s courage and skill.

Today, egg collecting is strictly regulated to protect puffin populations. While some limited egg collecting still occurs in certain areas under special permits, it’s no longer a widespread practice. Instead, these traditions are largely preserved through stories, museums, and historical reenactments, serving as a reminder of Iceland’s unique relationship with its rugged landscape and the creatures that inhabit it.

Hákarl (Fermented shark)

Hákarl, or fermented shark, is one of Iceland’s most notorious traditional foods. This dish, which dates back to the Viking Age, is made from Greenland shark or other sleeper sharks. The preparation process is unique: the shark meat is buried underground and pressed with heavy stones for 6-12 weeks, then hung to dry for several months. This fermentation process is necessary because the fresh meat of these sharks contains high levels of urea and trimethylamine oxide, making it toxic to humans if consumed fresh.

In modern Icelandic cuisine, hákarl maintains its status as a cultural icon, though its consumption has decreased significantly. It’s often served as part of the midwinter feast Þorrablót, a celebration of traditional Icelandic food. Small cubes of hákarl are typically served on toothpicks, often accompanied by a shot of brennivín, Iceland’s signature spirit, to help wash down its strong ammonia-like smell and fishy taste.

Hakarl drying on racks | Photo credit: MyImages – Micha via Shutterstock

While hákarl is not a common part of everyday Icelandic diets, it has found its place in the country’s culinary tourism. Many visitors to Iceland seek out this unusual delicacy to check items off their culinary bucket lists. Some Reykjavik restaurants, particularly those focusing on traditional Icelandic cuisine, offer hákarl as part of tasting menus or as a standalone appetizer.

Innovative chefs have also begun experimenting with hákarl in modern cuisine, incorporating it into contemporary dishes in small amounts to add a unique flavor profile. For example, some have used it in pâtés or as a flavoring for sauces, or combined with cream cheese, aiming to make the intense flavor more accessible to modern palates.

Despite its challenging taste, hákarl remains an important part of Iceland’s culinary heritage. It serves as a testament to the ingenuity of early Icelanders who developed preservation methods to survive in a harsh environment. Today, while it may not be a staple in Icelandic homes, hákarl continues to intrigue food enthusiasts and serves as a unique connection to Iceland’s past in its modern culinary landscape.

Other Must-Try Things to Eat and Drink in Iceland

Savory Dishes

- Hangikjöt: A popular dish of smoked lamb, often served during Christmas

- Plokkfiskur: Fish stew made with cod or haddock, potatoes, and onions

- Pylsur: Icelandic hot dog, often served with unique toppings

- Harðfiskur: Dried fish, usually cod, haddock, or wolffish

- Kjötsúpa: Traditional Icelandic meat soup with lamb and vegetables

- Svið: Boiled sheep’s head, a traditional dish

- Hrútspungar: Ram’s testicles pickled in whey

- Slátur: A type of blood pudding similar to haggis

- Kæstur hákarl: Fermented Greenland shark

- Saltfiskur: Salted cod, a staple in Icelandic cuisine, which is served with delectable Icelandic butter.

Dairy Products

- Skyr: A thick, yogurt-like dairy product high in protein

- Mysa: Whey drink, a byproduct of skyr production

- Ísey Skyr Bar: A popular skyr-based protein bar

Breads and Pastries

- Rúgbrauð: Dark, sweet Icelandic rye bread often baked using geothermal heat

- Laufabrauð: Thin, crisp bread decorated with intricate patterns, popular during the holiday season

- Flatkaka: Traditional flatbread, often served with butter or hangikjöt

Indulge your Sweet Tooth with these Dishes

- Kleinur: Traditional Icelandic donuts, often flavored with cardamom

- Pönnukökur: Thin pancakes similar to crepes, often served with jam and whipped cream

- Skúffukaka: chocolate cake with coconut frosting

- Vínarbrauð: Danish pastry filled with custard or jam

- Ástarpungar: Deep-fried dough balls, similar to donuts

- Hjónabandssæla: Traditional Icelandic oatmeal cake with rhubarb jam

Beverages

- Brennivín: Icelandic distilled spirit, also known as “Black Death”

- Bjórglögg: Warm Christmas beer with spices

- Gin: like many Nordic countries, Iceland has embraced gin distilling with aplomb! Try Old Reykjavik and the Pink Gin.

- Malt og Appelsín: A non-alcoholic Christmas drink mixing malt beverage and orange soda

- Icelandic Craft Beers: From breweries like Einstök, Borg Brugghús, and Kex Brewing

- Kókómjólk: Popular chocolate milk drink

- Lakkrís Shot: Licorice-flavored alcoholic shot

Arctic thyme is a key flavor of Icelandic Cuisine | Photo Credit: Fotokon via Shutterstock

Icelandic cuisine has come a long way from the survival food of early settlers to the innovative and diverse culinary landscape of today. Through centuries of adaptation to a harsh environment, periods of foreign influence, and recent economic upheavals, Icelandic food culture has maintained a strong connection to its roots while continually evolving. By embracing their history and unique ingredients while incorporating modern techniques and global influences, Icelandic chefs and food producers are creating a cuisine that is both deeply rooted in tradition and excitingly contemporary.

Resources Consulted for this Article

This article is a version of an enrichment talk I give on small luxury cruise ships. Researching this topic to create this article, inform my explorations of Iceland’s culinary scene, and to create my enrichment talk, I have found the following books to be incredibly useful and informative. You can get these and other wonderful books, podcasts, and other audio-visual information from my Destination Resources, which are curated lists for each region I work in. I hope you find them helpful and entertaining.

Access the Destination Resources here.

- Bjork, Katrin. From the North: A Simple and Modern Approach to Authentic Nordic Cooking.

- Gíslason, Gunnar Karl. North: The New Nordic Cuisine of Iceland [A Cookbook].

- Lacy, Terry G. Ring of Seasons: Iceland–Its Culture and History.

- Matt, Gisli. Slippurinn: Recipes and Stories from Iceland.

- Millman, Lawrence. Last Places: A Journey in the North.

- Nilsson, Magnus. The Nordic Cookbook.

- Nilsson, Magnus. The Nordic Baking Book.

- Rögnvaldardóttir, Nanna. Icelandic Food and Cookery

8 Hours in Vienna, Austria: The Best Things to Do

8 Hours in Vienna, Austria: The Best Things to Do

8 Hours in Vienna, Austria: The Best Things to Do

40+ Thoughtful Gift Ideas for Cruise Passengers 2024

40+ Thoughtful Gift Ideas for Cruise Passengers 2024

40+ Thoughtful Gift Ideas for Cruise Passengers 2024

The Must-Try Things to Eat and Drink in Iceland

The Must-Try Things to Eat and Drink in Iceland

The Must-Try Things to Eat and Drink in Iceland

8-Hours in Bruges, Belgium: The Perfect Itinerary

8-Hours in Bruges, Belgium: The Perfect Itinerary

8-Hours in Bruges, Belgium: The Perfect Itinerary

8 Hours in Bergen: A Guide to Norway’s Second City

8 Hours in Bergen: A Guide to Norway’s Second City

8 Hours in Bergen: A Guide to Norway’s Second City

8 Hours in Captivating Riga, The Capital of Latvia

8 Hours in Captivating Riga, The Capital of Latvia

8 Hours in Captivating Riga, The Capital of Latvia

Tangy Kefir Brined Chicken Shashlik

Tangy Kefir Brined Chicken Shashlik

Tangy Kefir Brined Chicken Shashlik

How to Make Shashlik: Recipes for Juicy Meat Skewers

How to Make Shashlik: Recipes for Juicy Meat Skewers

How to Make Shashlik: Recipes for Juicy Meat Skewers

Pierogi: Over 50 Recipes to Create Perfect Polish Dumplings

Pierogi: Over 50 Recipes to Create Perfect Polish Dumplings

Pierogi: Over 50 Recipes to Create Perfect Polish Dumplings

Amber & Rye: A Baltic Food Journey

Amber & Rye: A Baltic Food Journey

Amber & Rye: A Baltic Food Journey

really glad to have found this rich trove of your fabulous writing!

Thank you, Rebecca! Almost no one comments anymore, so this was a huge treat! so pleased you enjoyed the Iceland piece — this has become a massive obsession for me!